Reflections on Walking the Walk …..

Bienvenue and welcome back to Musée Musings, your idiosyncratic guide to Paris and art. This week, a few final reflections about the Camino. Next week, Barcelona. Where residents were so angry with the tourists overrunning their city this summer, that they squirted them with water pistols on the Ramblas. Which, as my friend Deedee noted, depending upon how hot it was, might have been as pleasant as it was aggressive.

As we were walking the Camino, I kept wondering about our medieval predecessors. Those pilgrims must have been poor peasants because if you had money, you could buy an indulgence or a relic or donate money to a church. And if you went on a pilgrimage, you would travel on horseback or by coach.

Here’s one example of a wealthy 12th century pilgrim. Eleanor of Aquitaine accompanied her first husband, the French King, Louis VII, on a Crusade to the Holy Land. That was in 1116. Her ladies-in-waiting had more carriages for their clothes than Louis had for his soldiers’ weapons. Their Crusade was as much a disaster as their marriage, which was annulled shortly after they returned from Jerusalem.

The people walking the Camino these days have enough money to stay at the hotels and inns and hostels that line the route. And enough time to walk for weeks or even months. Which is to say, these days, pilgrims aren’t poor.

That got me thinking about how many other things are the opposite of what they once were. Up until the late 19th century, poor people lived on the top floors of apartment buildings. That was before elevators. When the smaller apartments with the lower ceilings were at the top. Now, the upper floors in apartment buildings are the most expensive, with their high ceilings and spectacular views.

Here’s something else. Poor people didn’t get diseases from food high in fat and sugar because those ingredients were expensive. Gout, caused by a diet rich in fat was known as the "disease of kings.” Now artificial and trans fats are cheap and high fructose corn syrup is, too. Diseases they cause are mostly suffered by poor people.

Money aside, Ginevra and I simply could not understand how poor people had the time to walk the Camino. We assumed that poor people then as now, worked all the time. Siri must have heard us talking because this popped up in Ginevra’s instagram - the average medieval peasant worked less than half a year! (Fig 1)

Figure 1. Medieval peasants worked a lot less than you do!

Turns out, (J. B. Schor, The Overworked American: The Unexpected Decline of Leisure) the medieval calendar was filled with holidays. In England, there was Christmas and Easter, of course. And saints' days and rest days, too. All totaled, holidays made up 1/3 of the year. English workers worked more than their counterparts in France and Spain. In France, workers had 52 Sundays, 90 rest days and 38 holidays a year, that adds up to 180 days. In Spain, workers worked only 7 months a year.

And peasants knew the value of their labor. When there was more work than workers, workers demanded higher wages. And then they were willing to work only as many days as necessary to earn their customary income. At times like that, the number of working days was sometimes as low as 120 a year. Those days must have been long, during spring planting and fall harvest. But still, knowing that you would be working only half a year, a string of 12 hour workdays would have been bearable.

The mentality of American workers of the industrial age didn’t apply during the Middle Ages. No one thought that if you worked more, you would earn more and if you earned more you could buy more. Medieval workers chose time over stuff. They could go on pilgrimages because they had the time to walk for months.

When we were in Santiago, we unexpectedly stumbled upon a wonderful museum, the Museum of Pilgrimages. It was free, informative and topical. And, maybe not surprisingly, it was almost empty.

Here are a few of the things I learned there. The term "pilgrimage" can be used allegorically to express the similarity between a journey to a holy place and human life itself. The physical effort required to reach the pilgrim's goal is a “metaphor for the human spiritual journey, full of sacrifices, abnegation and heartache.”

The three main destinations for Christian pilgrims are Jerusalem, Rome and Santiago de Compostela. Going on pilgrimage to Jerusalem began with the Jews. The Old Testament instructed them to make a pilgrimage to Jerusalem three times a year, spring, summer, and fall. Jesus’ first pilgrimage to Jerusalem was when he was 12. His last pilgrimage to Jerusalem was when he was 33. He went for Passover.

Jerusalem was conquered by the Muslims in 638 and for long stretches, the Holy Land was under Muslim rule. The Crusades, which were more or less military pilgrimages to capture Jerusalem from Muslim control, were at best only temporarily successful. I mean, for the Christians.

Beginning in the second century, European pilgrims also traveled to Rome. It was easier to get there and safer, too. Rome’s bonafides are impeccable, of course. Rome is associated with early martyrs, among them the apostles Peter and Paul whose tombs are in Rome. And there are important relics in Rome. Also, the Pope lives there.

Santiago de Compostela became a pilgrimage destination much later, in the 9th century, when the body of St James was ‘discovered’. St. James (Figs 2, 3) and his brother, St. John the Evangelist were part of Jesus’ inner circle. They were with Him during the mostly important moments of His life.

Figure 2. Martyrdom of Saint James, Francisco Zurbaran, 1640

Figure 3. The headless body of St. James being put on a boat, with his head, too

There are two stories about how James’ body got to Spain. Here’s the one I like. Sometime after he was beheaded in Jerusalem (between 2 and 44 C.E.), St. James’ body was taken by a crewless ship (made of stone?) to Spain. So he could be buried where he had preached, in an area we now call Santiago. A wedding was taking place as the ship approached the shore. The bridegroom was riding a horse, which panicked when it saw the ship. The horse galloped over the cliff and into the sea. Miraculously, both horse and rider survived. They came out of the water, covered in scallops.

That’s how the scallop shell became the symbol of the Camino de Santiago. And scallop shells are everywhere - decorating churches and monuments, hostels and bridges. (Figs 4, 5) The meanings attributed to the shell are many and various, among them, the shell’s ridges and grooves symbolize the different routes of the Camino, the detours and hardships pilgrims encounter along the way.

Figure 4. Cross of St. James and Scallop Shell with my Hokas and Ginevra’s Allbirds

Figure 5. Shells on the bridge at Sarria

The symbol of the pilgrimage to the Holy Land is a palm branch or palm leaf. It’s a reference to Christ’s Entry into Jerusalem on a donkey. He was greeted by his followers who waved palm branches and laid them on the ground before Him. (Fig 6) Now the palm refers to the Sunday before Easter, Palm Sunday.

Figure 6. Christ’s Entry into Jerusalem, greeted by followers holding palm leaves and branches. Pietro Lorenzetti, Assisi, Italy, before 1348

The symbol of the pilgrimage to Rome are the keys of St. Peter. (Fig 7) I have seen the keys of St. Peter on architecture, sculpture and painting, but I have never associated the keys with a pilgrimage to Rome. By contrast, the scallop shell of the Camino de Santiago is always a reference to the Camino. Maybe it’s because Jerusalem doesn’t need pilgrims and neither does Rome. But Santiago de Compostela’s raison d’être is the Camino. People travel to the northwest corner of Spain because Santiago is the culmination of a pilgrimage. Or maybe it’s just good marketing. Pilgrims bring a lot of money into local economies along the Way.

Figure 7. Christ giving keys to St. Peter, Perugino, Sistine Chapel, 1481

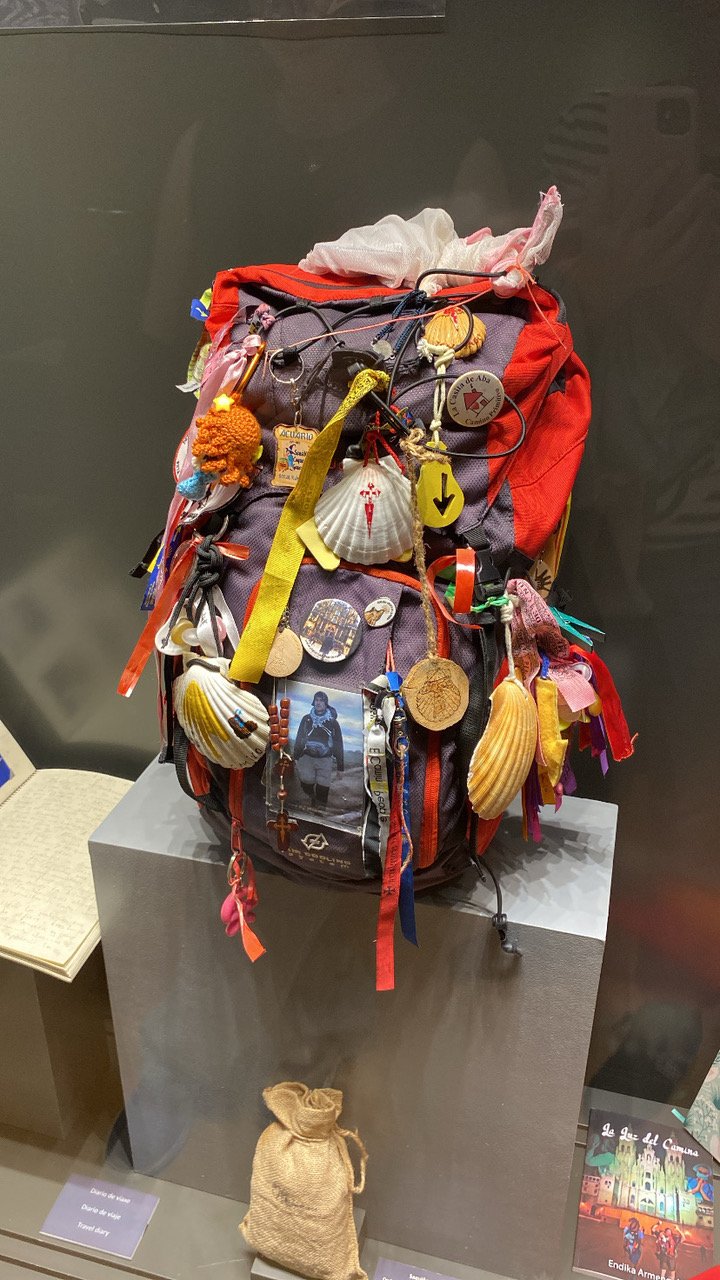

The museum helped me contextualize our experience answer my questions. One of the things I wondered about was all the merchandise. There is merch for sale everywhere along the Camino. Some of it obviously made in China, some of it made by the artisans selling it. Most of it, but not all of it, related to the Camino. There were scallop shells and replicas of the cross of St. James and replicas of the cement posts with the arrow, pointing the Way. There were hippies along the Camino, too. One was selling ‘good vibes,’ several were selling the kind of jewelry I remembered from craft fairs when I was in college. And Abdul was making beautiful wax stamps (Fig 8-10) By the time we got to Santiago I thought I was immune to all the teeshirts, sweatshirts, hats, etc. I wasn’t! I succumbed and bought a sweatshirt and a few pins (Fig 11 and 11a).

Figure 8. A backpack covered with shells and pins bought along the way

Figure 9. Abdul making wax stamps

Figure 10. The wax stamp Abdul made for me - Shell and Cross

Figure 11. Ginevra and me in our matching sweatshirts

11a. Camino pins!

Merchandise, aka souvenirs, are not a modern phenomenon. One of the museum displays discusses them. Initially, souvenirs were made of jet (a gemstone derived from wood that has changed under extreme pressure). According to Wikipedia, “at the end of the Middle Ages, the trade of religious objects and amulets made of jet” (was highly developed) in Santiago de Compostela, (because of) sales to pilgrims traveling the Camino de Santiago.” The museum explains that jet souvenirs were made by local craftsmen and were sold under the auspices of the Church. In addition to scallop shells, there were crucifixes, amulets, necklaces, rosary beads, and sculptures of St James. (Fig 12) Now, it’s an unrestrained free-for-all, the result, according to the museum, “of the globalization and commercialization of modern tourism.”

Figure 12. Souvenirs from the past - shell, cross, rosary beads, ampule

So, that answered my ‘stuff’ question. I also wanted to know about apparel. Specifically, what did pilgrims wear as they walked. The museum had a display of pilgrim attire, past and present. Turns out, people have been obsessing about what to wear on the Camino long before Ginevra and I turned our thoughts to the issue. The earliest pilgrims wore walking clothes: capes, cloaks, hats and sturdy shoes. Over time, “the pilgrims’ outfits became increasingly standardized with the staff. the basket, the purse, … (and) the gourd in which to carry water or wine.” (Figs 13-14) As they traveled, pilgrims “sew(ed) insignia from the different shrines .. they had visited into their clothes, including scallop shells and miniature staffs typical of the Camino.” Now pilgrims wear sportswear created for maximum comfort and utility, like our Hokas! And continue to buy scallop shells, pins and patches to put onto their backpacks. (Fig 15)

Figure 13. Pilgrim with Hat, Shell, Gourd, Cape, Staff, Sporran (or purse)

Figure 14. 14th century pilgrim wearing Hat and Cape decorated with Shells, a staff and rosary beads

Figure 15. A modern pilgrim with shell, gourd, hat, jacket, sleeping roll

Pilgrim safety and health have been concerns ever since people began walking the Camino. To keep them safe, “…rules were established to protect the pilgrims.…”Initially, “the vulnerability of the walker to attack from wild animals, bandits and criminals was combated by organizing pilgrims into groups. They would often travel with merchants who were transporting their goods in carts or on the backs of animals.” For pilgrims who became ill, hospitals sprang up along the Camino. In Santiago, the hospital founded by King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella in 1499 was built to treat sick pilgrims. The hospital is now a Parador, a five star luxury hotel. (Figs 16, 17)

Figure 16. Entrance, Parador, Santiago de Compostela

Figure 17. Interior Cloister, Parador, Santiago de Compostela

We flew to Santiago, took a taxi to Sarria, then walked back to Santiago. Which still seems self indulgent. And yet, from the beginning, most “pilgrims from England and other parts of northern Europe would often sail to a port in France or Spain and then continue the journey to Santiago on foot.” People still mostly walk the Camino today but several groups of pilgrims on horseback galloped by us, requiring us to be even more vigilant to avoid stepping on horseshit. Cyclists, thank goodness, have their own route, (Figs 18, 19, 20) although sometimes they rode on ours, mostly politely. And it was heartening to see a group of paraplegic pilgrims on motorized wheelchairs.

Figure 18. Horses waiting to be saddled up to walk the Camino

Figure 19. Marker for Bicycle Route on the Camino

Figure 20. Nearing the end of our Camino, only 10 km to Santiago de Compostela

In one of the last displays, we are told that there is no one reason that people walk the Camino. Some people walk “out of pious devotion or to ask for the grace of God.” Other people walk as a way of doing penance, of earning an indulgence. In the past, prisoners could choose to go on pilgrimage rather than go to jail. Without passing judgement, the museum tells us that “(t)oday those with religious motivations are joined by others making the journey for cultural, ecological, (and) sporting…. reasons. Some people use it as a time to meditate, others as a way to escape.”

When we finished our pilgrimage, I thought that walking the Camino was a ‘one time only’ experience for me. Now I’m reconsidering. Thanks to everyone who sent Comments last week, they are much appreciated. Gros bisous, ‘Dr. B.’

Comments on Walking the Walk:

What a delightful read!! Thank you for bringing us along, and especially for the beautiful pictures that made the journey so vivid... my mouth literally watered at some of your food pictures (and yes, I know the meaning of the word "literally." 😀) I had only a vague understanding of this pilgrimage, but you have motivated me to learn more, and perhaps even do it myself someday, now that I know it's manageable for single women, and even women who have been widowed after 40 years. You are an inspiration, Dr. B, and Ginevra is lucky to have such an adventurous personal tour guide! Thank you!!!

Bonnie in Rhinebeck, NY

Wow! You did it. Mazel Tov as they say. Your pre planning was amazing, and it paid off. You should be proud.

By the way, Ben and I had lunch in that Parador. It was delicious, especially the bread! But disconcerting as the room we had lunch in had a magnificent altar piece at one end of the room. It sort of felt sacrilegious to be eating there.

So glad you made it to the end safe and sound. Deedee

Congrats on the Camino completion. Something I always wanted to do but now, I fear its too late. My knees are pretty much shot and unless they miraculously heal I guess it is not in the cards.

Curious as to the model of Hoka that you have . Mine are Bondi 8 and I do love them!

On the subject of politics, you have a perfect right to express your opinion in your blog(especially when it agrees with mine). Seriously, I am fearful for our country and our democracy as are all of my friends. Send positive vibes for us. and our future generations. Shirley

Never had the slightest interest in doing the Camino walk until I read your charming, challenging account. Loved the ups and downs, the solutions to problems. I’ve been enjoying your musings since they began, as I lived in Paris as a student and more, went incessantly to museums, galleries, and other wonderful spot francaises, and live in the Bay Area now. Thanks so much. Liz

Dear Beverly, I so enjoy your blog. Thank you! I’m a retired French teacher (high school) and have great memories of students’ glee when they were seeing. France for the first time. Your enthusiasm brings back some of the happiness I have found when exploring Europe with others. I have never walked the Camino so I have loved today’s pictures and comments about your experience. Congratulations on your accomplishment!

Madeline B. In Oregon

Hello Beverly, I don't know how I happened upon your blog but it one of the only ones I read, as it is interesting, amusing and well-written. I wrote to you simply to say that as well as to say that I am a University of Michigan grad as well. I got my B.A. there before moving to France, returning to Northwestern Medill School of Journalism for a Master's and then returning to France for.... life. I have lived here for 53 years with my French husband, worked as a freelance journalist and taught journalism. I have also written a few books about France and the French, one of which you may know, "French Toast". Again, congratulations on your Musée Musings and thanks for sharing your erudition (which you wear lightly) and experiences. Best wishes, Harriet, Paris author (French Toast, French Fried, Joie de Vivre and Final Transgression)

Dear Dr. B Most interesting essay. Yes, part of the journey would have been enhanced with meeting of other pilgrims. My ROAD SCHOLAR trips, even as a single, were

enhanced by the other participants.Yet, surprised that you didn’t have a couple of frozen croissants in your backpack on the first day to enjoy. Lady with the sandwich & an Auschwitz survivor reflects my current reading of RECKONINGS by Mary Fulbrook [Oxford , UK] on the ‘legacies of Nazi persecution and the quest for justice.’. Appalling account that less than 1% of the one million involved with the Holocaust were ever brought to justice. Shocking to read that 3700 women were guards in the many killing centers / camps YET overwhelming majority never prosecuted. BTW are your shoes still wearable after the Camino ?? Bill, Ohio