Projet Proust: Or how I became a Proust-head

Marcel Proust. Un Roman Parisian, Temporary Exhibition, Musée Carnavalet

Bienvenue and welcome back to Musée Musings, your idiosyncratic guide to Paris and art. This week was mostly a lazy one, enjoying the pleasures of Paris. We took turns reading poems by Rimbaud in French and in translation. In the Place des Vosges while eating sushi. Rimbaud stopped writing poetry at 20 and began traveling the world. Among his ports of call were Java, Alexandria and Ethiopia. So, sushi seemed like an acceptable choice. Another day, we ate falafels along the Seine, reading Hemingway on Paris, A Moveable Feast.

Of course we got to a museum. The Palais Galliera for '1997 Fashion Big Bang.’ The exhibition title taken from an article which appeared in Paris Vogue that year. With video footage, photos and fashion, the exhibition was as rich in cultural history as it was in fashion history. When we got home, we stayed on topic and watched Robert Altman’s 1994 film Pret-a-Porter. The cast, a who’s who of fashion and film celebrities included Cher who admitted to being a fashion victim as well as a perpetrator. The film was surely pertinent then, it certainly is now, nearly 30 years later.

Today’s topic isn’t paintings or poetry but rather the challenge I set myself at the beginning of the year. To finally begin reading Marcel Proust’s masterpiece, A La Recherche du Temps Perdu. Robert Gottlieb, Robert Caro’s long time editor, died this week. And I thought about all the words Proust wrestled with as he wrote his masterpiece. In the New Yorker appreciation, we learn that Gottlieb read War and Peace in a weekend, Proust’s seven volumes in as many days.

Since the Proust celebrations began in 2021, honoring the 150th anniversary of his birth and the centennial of his death, I have been reading around and about Proust. During those two years, I saw three exhibitions here in Paris that explored Proust’s life and life’s work from different angles. Each time I went to an exhibition, each time I researched and wrote another review, I became more and more convinced that ‘about and around’ wasn’t enough - I had to read the mother text.

In fact, Proust was in the air even before those exhibitions. For example, the exhibition about the society painter, Giovanni Boldini at the Petit Palais was called Les Plaisirs et les Jours, the title of Proust’s first book, published in 1895. Boldini’s portraits of women in gorgeous ball gowns and men looking like fashionable dandies - evoke the Belle Époque, Proust’s epoch. I was captivated by Boldini’s portrait of the impossibly thin, improbably elegant Comte de Montesquiou, Proust’s model for Baron de Charlus. (Figure 1)

Figure 1. Comte de Montesquiou, Giovanni Boldini, Proust’s model for Palamède de Guermante, baron de Charlus,

Another exhibition, this one at the Musée d’Orsay, celebrated Yves Saint Laurent. Under the grand horlage (clock), the curators recreated the 1971 Bal Proust given by Baron Guy de Rothschild to commemorate the centenary of Proust’s birth. For the event, Saint Laurent was commissioned to create costumes for Jane Birkin, the Baroness de Rothschild and others. (Figure 2) Yves Saint Laurent said, “Like Proust, I am fascinated by my own perceptions of a world in transition.”

Figure 2. Yves Saint Laurent exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay, the 1971 Bal Proust costumes by YSL

Proust sightings have not disappeared. The exhibition currently at the Petit Palais on Sarah Bernhardt has a section on Proust. In Le Recherche, Bernhardt is Berma. She was an intimate of the Proust family, having had sexual relations with both Proust’s father and his mother’s brother. I don’t know the details - simultaneous, sequential, who was first - please don’t ask me, I don’t know!

When I decided to start reading A La Recherché du Temps Perdu, I was pretty sure that, as a perennial student, the best thing for me would be to find people who were also tackling Proust. Conveniently, I found a Proust group at the American Library that met once a month. When I contacted the group’s leader in January, I learned that the group had already made its way through Book One, Swann’s Way, the previous September through December.

Why had they started reading in September rather than January? Because dear friends, the rentrée reigns supreme in France. September is the beginning of the year. It’s the return to reality and responsibility after an idle summer spent at the sea shore or in the mountains. September has always been the beginning of my year, too. Maybe because I went to school for so many years, taught school for so many years, and had kids in school for so many years. Perhaps the French focus on the rentrée is why I am so comfortable here. The French organize their lives the way I organize mine.

Like you, I have known about Proust forever. Perhaps like you, too, I figured that there were enough books in English, also long and with a reputation for being difficult, that I should try to read before tackling Proust. And the people I kept bumping into who were reading Proust or who were re-reading Proust, were more like acolytes than aficionados. It was a little creepy. Now I have begun to bore my French friends with my constant references to Proust, so maybe I have turned that corner already.

At the Proust group leader’s suggestion, I purchased the Moncrieff/Kilmartin translation of the Pléiade edition of Swann’s Way and Within A Budding Grove. As I began reading, I was delighted to find so many passages that I already knew by heart. But more than that, I discovered that rather than being off putting, the text was inviting. I was savoring what I was reading. I put post-its at references to art, especially painting. And post-its at references to meals and ingredients. Quickly, my book fluttered with post-its.

Kilmartin’s update of Moncrieff’s translation was prompted by Kilmartin’s contention that Moncrieff’s prose “tend(ed) to the purple and the precious” whereas even though Proust’s writing is ‘complicated, dense and overloaded’, it is “essentially natural and unaffected”. Kilmartin’s success in ditching the preciousness was probably one of the happiest surprises for me as I read.

Proust writes in the first person. He is telling his story. As he recounts incidents he remembers, he shares feelings and sensations. His sense of himself as a child, as a boy, as a young man (he is in his late teens when volume 2 ends, which is as far as I have gotten) is so strong, and the word pictures are so sure, that we are with him every step of the way. Yes, people complain that his sentences never end, and it is true that some (many) go on for pages. But I find myself getting so immersed in the scenes he paints that I don’t need punctuation. I don’t need periods and paragraphs.

Here is where I put the first post-it. It is Proust’s description of his father one evening after the family’s dinner guests have departed. The narrator is awake and asking for his mother. Rather than getting angry with his son, he encourages his wife to go to their son’s bedroom and comfort him. Proust describes his father this way: “…a tall figure in his white nightshirt, .., standing like Abraham in the engraving after Benozzo Gozzoli … telling Sarah that she must tear herself away from Isaac.” (Figure 3)

Figure 3. The Sacrifice of Isaac, after Benozzo Gozzoli, print by Carlo Lassino, 1806

I had forgotten this passage when Ginevra and I visited the Sinopie Museum in Pisa last week. But then I saw the sinopia, (underpainting of a fresco) by Gozzoli to which Proust refers. I was already awash in my own memories of the first time I visited this museum with my husband and then, when I remembered my first Proust post-it!

The next post-it refers to something the narrator’s grandmother says - that she prefers engravings to photographs. Proust understands her preference, noting that an old print after Leonardo’s Last Supper would be better than a recent photograph. Because the print can “show us a masterpiece in a state in which we can no longer see it today”. And then, there I was, in Milan, looking at Leonardo’s masterpiece in its current, truncated form. The bottom chopped off many years ago when the priests who ate in the dining room where it is, wanted a more direct route to the kitchen which is behind it. The Apostles’ feet are gone, cut off to make a door. We know the full painting from a contemporary copy of it that is now at the Chateau d’Ecouen. (Figs. 4, 5)

Figure 4. Last Supper, Leonardo de Vinci, Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan

Figure 5. Copy after Last Supper, Leonardo de Vinci, Chateau d'Ecouen

Both of those post-its came before the magical madeleine moment! And what is truly magical about that moment is Proust’s realization that it is not drinking the tea and dipping the madeleine that will transport him since “the truth I am seeking lies not in the cup but in myself.” Doesn’t that sound awfully close to what Julius Caesar said to Brutus, ““The fault lies not in our stars, but in ourselves.” Yes, Proust is speaking about the past and Caesar about the future, fate, but, at least in the English translation, they strike me as echoes of one another, the past as prelude to the present and future.

And so it goes throughout the book, so many references to artists and images. References that are so smart, so thoughtful. References to art and food were what I was expecting to find. What I wasn’t expecting was to become so fully immersed in Proust’s sometimes sad, sometimes funny, reflections on a wide range of ideas and emotions. But I do agree, his thoughts are too dense, too sophisticated for 15 year old high school students, the age in France when Proust appears on the school curriculum.

With 600 pages under my belt - February was my first meeting with the Proust reading group. The discussion was far-ranging and free-wheeling. We talked about Gilberte, the first object of the narrator’s desire. She is the daughter of the erudite and wealthy Charles Swann and his mistress, then wife, the beautiful demi-mondaine, Odette de Crécy, Who looks like a Botticelli Madonna. (Figure 6) Which is not a point in her favor, Swann doesn’t really like Botticelli’s women.

Figure 6. Zipporah, daughter of Jethro, detail from Sandro Botticelli, “The Trials of Moses,” Sistine Chapel

I said that I was surprised that Gilberte was not shunned by the other children because of her mother. Children listen to their parents’ conversations and children can be so cruel. I was thinking about the humiliation the mother of the artist Edouard Vuillard suffered as a child because her own mother was not married when she was born. And while it is true that Swann attends many social functions by himself and Odette’s salons are frequented by men whose wives refuse to come, Gilberte, their beautiful and beloved daughter, isn’t punished for her father’s predilections or her mother’s former profession.

Since I caught up in my reading by February, I stopped devouring Proust’s opus and began savoring it. Normally, I read newspapers in the morning, magazines at noon and books at night. But that doesn’t work with Proust. You need to be fresh to read his words. I read Proust with my morning coffee. Since we discuss 100 pages each month, I have adopted this schedule. From Monday to Friday I read 10 pages a day for 10 days in English. Then I read the same text, 10 pages a day, in French.

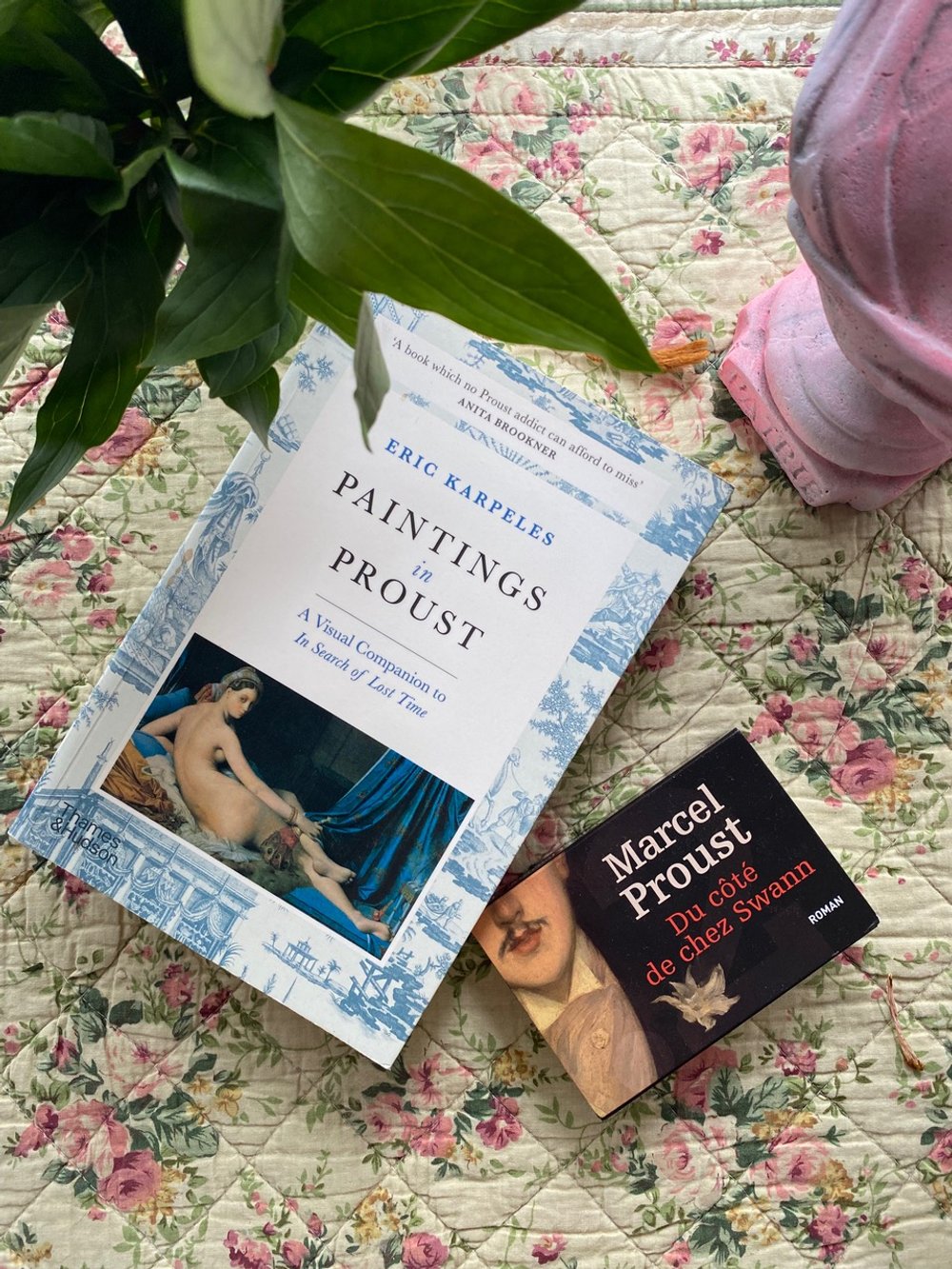

The French text I used for Swann’s Way was a book a French friend gave me. The book is tiny - the size of a 3” x 5” index card. The pages are Bible thin. Yes, there are over 800 of them, but it’s an un-intimidating fun size. (Figure 7)

Figure 7. My fun size Du côté de chez Swann, Marcel Proust next to the book that made me a ‘Proust-head’

At the March meeting, one member of our group admitted to being obsessed with the book’s Endnotes. There are very few Endnotes in the English edition and the ‘fun’ size volume of Du côté de chez Swann didn’t have any Endnotes at all. So, when I bought À l’ombre des jeunes filles en fleurs at FNAC, at the Gare de Montparnasse, (I had a choice of 4 or 5 editions) just before getting on the train for Bordeaux, I made sure that the volume I bought had Endnotes. And it’s true, they are habit forming!

I wonder if, at any random train station in London, you can pick up a copy of James Joyce’s Ulysses (In a list of 10 books nobody ever finishes reading, Ulysses is #1, La Recherche du Temps Perdu is #3). Or if, at an airport in any U.S. city, you can find a book by Faulkner, for example.

Our last meeting for the year is next week. Then summer break. I can’t decide whether to reread the first two volumes or start reading the third and fourth volumes to get a head start! A delightful dilemma.