Painting for the Joy of Painting

Suzanne Valadon: Artist’s Model to Artist

Bienvenue and welcome back to Musée Musings, your idiosyncratic guide to Paris and art. This week, a review of an exhibition that will be in Paris until the end of May, at the Pompidou, called simply, Suzanne Valadon. I’m sure many of you have heard of her, either because you know one of her paintings or because you have visited her studio at the Musée de Montmartre. (Figs 1, 2)

Figure 1. Femme aux bas blanc, Suzanne Valadon, 1924

Figure 2. Reconstruction of Suzanne Valadon’s studio in Musée de Montmartre

Before we get to Valadon, the temporary exhibition at the Musée de la Chasse et Nature (thru April) merits your consideration. I wrote about this museum last year and even though I knew what to expect, it was every bit as lovely. Yes, I know, taxidermy hardly suggests the word lovely and yet this museum, fully aware that it has to work harder to lure visitors, does so with a gentle sense of humor. Tucked in with all the stuffed birds and beasts are remnants of past temporary exhibitions. An eclectic assortment of paintings, sculptures, installations and videos are now part of the permanent collection. And pop up, often where you least expect them. (Figs 3, 4)

Figure 3. Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature,

Figure 4. Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature

The artist there now is Edi Dubien, a trans man who has a particular affinity with fragile and vulnerable animals. There’s a delicacy to his work that is simultaneously charming and cautionary. This is how the museum describes the exhibition. “Edi Dubien, a self-taught French artist born in 1963, is known for his works of profound poetry and moving humanity, which explore themes related to identity, childhood and the relationship between humans and nature. In his works, children with melancholic gazes, often made-up animals and plants develop relationships of exchange, cooperation, metamorphosis and, certainly, consolation. … Edi Dubien celebrates otherness and the freedom to be oneself.…” (Figs. 5-7) With D.E.I. programs in the United States gone with the stroke of a malicious pen, would any museum dare mount this exhibition in the U.S.

Figure 5. Edi Dubien Temporary Exhibition, Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature

Figure 6. Edi Dubien in temporary exhibition room, Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature

Figure 7. Bear holding bouquet, part of temporary exhibition by Edi Dubien, Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature

En route to the museum, I stopped by the Musée Carnavalet. The permanent collection is always free and I wanted to visit the Bijouterie of Fouquet, designed by Alfred Mucha, (Fig 8) the master of Art Nouveau. It had been featured in the exhibition I saw last week on Pearls. And of course, I never go to the Carnavalet without visiting Proust’s bedroom. His bed is there, so is a chaise longue, a few cork tiles to show how he soundproofed his room and the top coat he wore whenever he dared to venture out. There’s a little slide show featuring a parade of Proust people, sometimes only thinly disguised in his A la recherche de temps perdu. If you haven’t been, you must go, even if you’ve yet to open your copy of the Madeleine Master in French or English. (Fig 9)

Figure 8. Reconstruction of Bijouterie Fouquet, Musée Carnavalet

Figure 9. Reconstruction of Proust’s bedroom, Musée Carnavalet

On my way home, I stopped at Brigat for an almond croissant and a chocolate/pear crumble. (crumbles are a Brigat speciality), both were exceptional. (Fig 10)

Figure 10. Chocolate / Pear Crumble from Brigat, on a Make-a-Plate by Ginevra, 2014

So, Suzanne Valadon. Her life (1865-1938) overlapped with two female artists whose work I’ve recently reviewed. Mary Cassatt (1844-1926) and Tamara de Lempicka’s (1898-1980). Unlike Mary Cassatt, Valadon grew up poor. Society imposes less restrictions on poor women because society has less to lose when a poor woman goes rogue, does what she wants to do, what she has to do to survive. Without societal constraints, Valadon pushed boundaries, asserted herself. Tamara was, like Valadon, a free spirit. Able to do what she wished, not because she was poor, but because she was an outsider and because - timing. Tamara found success between the wars, when European and American women could live their most authentic lives. Valadon’s bohemian lifestyle included many lovers, who (unlike Tamara’s) seem all to have been men.

Suzanne Valadon was born in 1865 to a poor single mother. She left school at 11, had a variety of jobs, seamstress, circus performer and then became an artist’s model at 14. She posed for Renoir, Toulouse-Lautrec, Berthe Morisot and others. (Figs 11-13)

Figure 11. Dance at Bougival, Auguste Renoir, 1883 (Suzanne Valadon, model)

Figure 12. The Hangover, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. 1889 (Suzanne Valadon, model)

Figure 13. Tightrope Walker, Berthe Morisot, 1886 (Suzanne Valadon, model)

Toulouse-Lautrec, with whom she is said to have had a tempestuous affair, suggested she change her name from Marie-Clémentine to Suzanne. Because a young girl who poses nude for old men should be called Suzanne. The reference - the biblical story of the beautiful young bride Suzanne spied on by the lecherous Elders. (Fig 14)

Figure 14. Suzanna at her bath spied upon by Elders, Tintoretto (bald elder, front left, standing elder, back left)

Suzanne had always been good at drawing and as she posed, she watched the artists who painted her and she learned from them. She decided to become an artist and bided her time until she could. The artists for whom she posed greeted her decision in a variety of ways. Jean-Jacques Henner said, according to a posthumous account, that Valadon's painting were ‘bad,’ And that he was astonished that "it was through [his) contact that the idea had come to her to paint”. , Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, for whom Valadon was the model for both female and male figures in his large scale compositions, “did not support Valadon when she wanted to embark upon an artistic career,” He allegedly told her, “you are a model, not an artist.”

But she did have her champions. The sculptor Bartholomé urged Valadon show her drawings to Degas. He was kind to Suzanne and supportive, too. He said, ‘You are one of us.’ Valadon never posed for Degas, "but he opened the doors of his studio to her, taught her soft ground etching on his own press and bought many of her drawings.”

Valadon’s personal life was chaotic. She was 18 and single when she gave birth to a son. A male friend of hers, although probably not the baby’s father, signed documents that gave the baby his last name, Utrillo. She continued modeling while her mother minded Maurice. In the early 1890s, Valadon had a torrid love affair with her neighbor the composer Erik Satiee. He sketched her on music paper, she painted his portrait, one of her very first. (Fig 15) After Valadon ended the affair, Satie was devastated. He composed ‘Vexations’, an score whose theme repeats 848 times and can last up to 24 hours. The work was found after his death. You can hear bits of it playing near his portrait.

Figure 15. Erik Satie, Suzanne Valadon, 1992-93

In 1895, when Valadon was 23, she married a wealthy businessman, Paul Mousis, who was as much a free spirit as she was. Economic stability meant Valadon could become an artist in earnest. For 13 years, they shared an apartment in Paris and in a house in the suburbs. She had a maid and a car and enough money to buy art supplies.

Her mother minded Maurice (Figs 16, 16a) but he was a difficult child, frequently falling into a rage. Suzanne’s mother gave him diluted wine to calm him down. He didn’t calm down but he did become an alcoholic and then an addict. Suzanne tried to calm him down by showing him how to draw, that didn’t calm him down either but he did become an artist.

Figure 16. Maurice after the bath with his grandmother, Suzanne Valadon, 1892

Figure 16a. Maurice as a child, Suzanne Valadon, 1894

Suzanne once said, ”I belonged entirely to my son Maurice Utrillo and to my painting, two great things that I adore, but two great problems too, believe me!"

Suzanne and Moisis gradually grew apart - whether she was bored with money or with Moisis many mistresses, by 1908, they were separated. That same year, Maurice brought a fellow art student home with him. His name was André Utter, he was 23. Suzanne was 44. They became lovers. The following year, they married. Maurice’s friend became his step-father. That couldn’t have helped his mental state!

In the early 1920s, a Parisian art dealer paid Valadon a large sum for an agreed amount of work. She bought a dilapidated chateau. From then on, the three of them spent summers at the chateau and winters in Montmartre. They painted and they argued.

Valadon continued to paint Into her 60s but poor health slowed her down. During one of her hospital stays, a friend, the widow of an art collector, offered to take care of Maurice. Which she did so well that they became lovers and then were married. Valadon, jealous of this competition for her son’s affection, worried that it was about money. But it was just what he needed, he sobered up, calmed down and lived to the age of 71.

The exhibition divides Valadon’s works into categories, lets look at a few of them, starting with her self portraits. The self-portrait from 1883 when she was 18, is one of her earliest known works. (Fig 17) She looks directly at the viewer. The look is proud, maybe even severe but for a model accustomed to having her portrait painted, it’s not at all vain. The signature must have been added later, after Maria had become Suzanne.

Figure 17. Self Portrait, Suzanne Valadon, 1883

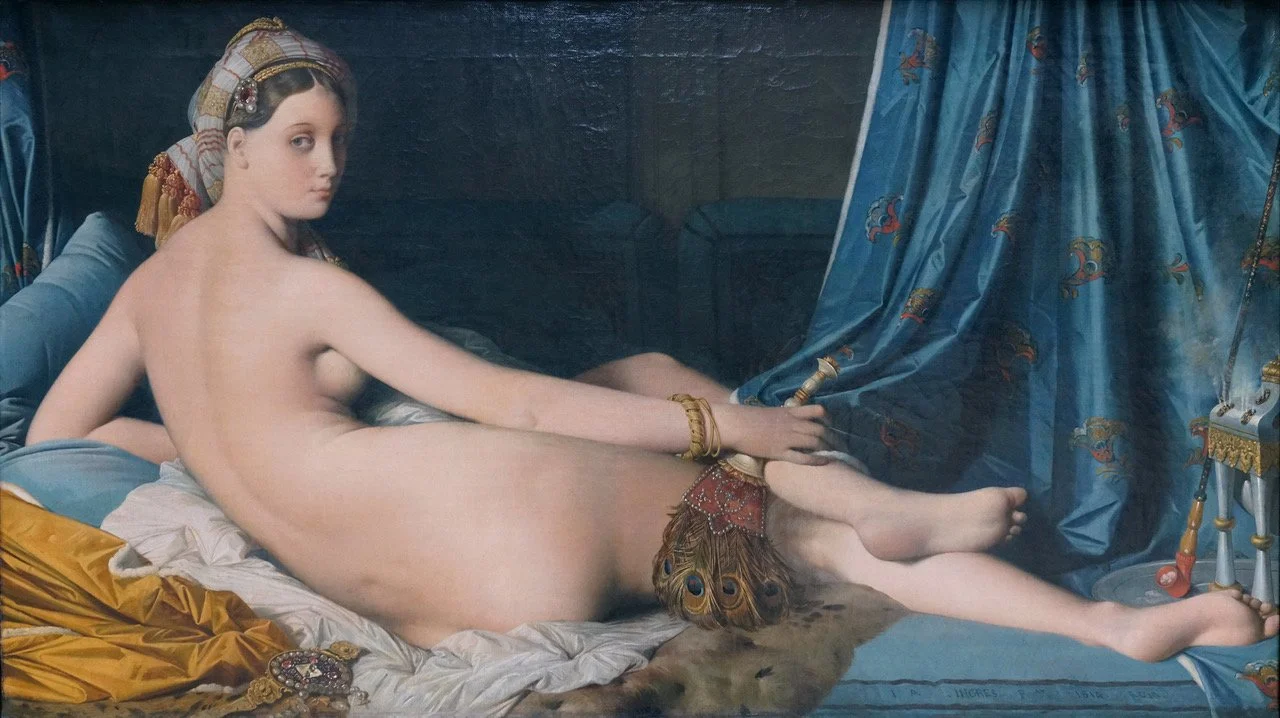

The Blue Room, a self portrait from 1923 is a flurry of patterns and colors. (Fig 18) The artist’s pose is reminiscent of both Ingres’ and Manet’s Odalisque. (Figs 19, 20) She presents herself as a proud and independent woman who neither welcomes the viewer’s gaze nor returns it. Her sturdy body is not languid, it is at rest. With striped pajama bottoms and a cigarette in her mouth, there is not a hint of eroticism. On the bed by her side are two books, one a novel, the other an art history book. This is a woman waiting for us to leave so she can get back to enjoying her solitary interests.

Figure 18. The Blue Room, Suzanne Valadon, 1923

Figure 19. Odalisque, J.A.D. Ingres, 1814

Figure 20. Olympia, Edouard Manet, 1863

The final self portrait was painted in 1931 when Valadon was 66 years old. (Fig 21) She presents herself as she was - gaze stern, lips pursed, breasts slightly sagging. According to the curators, this was the first nude portrait of an aging artist. In 1980, 70 years later, the 80 year old Alice Neel completed a self portrait begun 5 years earlier. (Fig 22) Like Valadon’s, there is an unflinching regard and lack of vanity or pretension.

Figure 21. Self Portrait, topless, Suzanne Valadon, 1931 (age 66)

Figure 22. Self Portrait, Alice Neel, 1980 (age 80)

When Suzanne was starting out, she couldn’t afford models so she drew and painted her family and the places she knew and lived. In 1912, she painted Portrait de Famille (Figs 23, 23a) it’s the only painting in which she appears with her lover (standing, looking to the left), her son (seated, his chin in his hand, an iconographic reference to melancholia), and her mother, (on the right with all her wrinkles showing). Valadon is in the center of the composition. She holds our gaze, well actually she’s looking at herself in a mirror. But she’s the center of the composition, the center of the family.

Figure 23. Self portrait with Family, 1912

Figure 23a. Melancholia, Albrecht Durer, 1514 (Melancholy rests her chin on her hand like Maurice)

Valadon was a little more carefree when she painted the places where she lived, like the 1928 Garden on Rue Cortot, seen from her studio window.. The building, supposedly the oldest house on the Butte de Montmartre, is now home to the Musée de Montmartre, where Valadon's studio has beer reconstructed. (Fig 24)

Figure 24. Garden on Rue Cortot, Suzanne Valadon, 1928

There are two paintings of the artist’s niece and her daughter done 8 years apart which merit our gaze. In 1913, Valadon depicted her niece, sitting in an armchair with her daughter sitting at her feet, on a cushion, with a doll on her lap. (Fig 25) The young girl stares at the viewer, her mother looks away. The curators suggest that the construction of the space alludes to the difference in age of mother and daughter.

Figure 25. Marie Coca with her daughter, Gilberte, 1913

Eight years later, (1921) mother and daughter are back. Now they’re in a bedroom. (Fig 26) The mother dries her daughter’s back. The daughter looks at the mirror in her hand. The doll is still there, but it’s on the floor, abandoned. The girl is interested in her own reflection, not in playing with dolls. But it’s strange. The girl’s breast suggest maturity but the bow in her hair suggests childhood. She’s betwixt and between, at the cusp. The painting reminds me of paintings by the surrealist Paula Rego, filled with children who look too old, adults who look too small and weird stuff going on. (Fig 27)

Figure 26. Marie Coca with her daughter, Gilberte, 1921

Figure 27. The Family, Paula Rego, 1988

The mirror was a recurring element in Valadon’s paintings. In traditional Vanitas paintings, mirrors remind the young women staring into them that youth and beauty are fleeting. (Fig 28) For Valadon the mirror, whose practical function is often diverted, is more a reflection (pun intended) of the passage of time from childhood to maturity.

Figure 28. An example of a ‘Vanitas’ painting - the beautiful young woman stares at herself in a mirror

Valadon painted nudes frequently. She didn’t idealize the women she depicted. As a female, the artist’s (normally male) gaze, the viewer’s (normally male) desire and the model’s (normally nude female) vulnerability aren’t at play.

And yet there is Valadon’s 1923 portrait of her maid Catherine, nude, reclining, on a panther skin, on a red rug, on a flowered rug, on the floor. (Fig 29) The body, curvaceous, the breasts, ample. Yet Valadon’s model has agency, it’s her desire that we sense. Unlike Courbet’s sleeping Bacchante for whom the male gaze is paramount or Tamara de Lempicka La Bel Rafaela for whom the gaze of the female artist dominates.(Figs 30, 31)

Figure 29. Catherine lying nude on a panther skin, Suzanne Valadon, 1923

Figure 30, Bacchante, Courbet, 1844-47

Figure 31. La Belle Rafaela, Tamara de Lempicka, 1927

The setting for Valadon’s 1919 Black Venus (Fig 32) is a forest. The athletic black model steps forward, her hand on a towel draped on a pile of rocks, a stand-in for a pedestal. With her other hand, she hides her pubis in a traditional Venus Pudica pose (Fig 33). As the curators note, without exoticism and condescension, Valadon’s black model has a become a goddess and the definition of classical beauty has been enlarged.

Figure 32. Black Venus, Suzanne Valadon, 1919

Figure 33. Capitoline Venus Podia who covers both her breasts and pubis. Valladon’s Venus doesn’t cover her breasts but both modest Venuses have a towel or garment nearby

In the painting, Two Figures, from 1909,(Fig 34) the two women aren’t posing, they don’t seem to notice that they are being painted. One leans back onto a sofa, partially wrapped in her towel. The other stands, pulling on her robe. The curators suggest that this setting is probably a brothel in Montmartre. There’s nothing voyeuristic going on, the painting reminds me of similar works by Toulouse-Lautrec. (35)

Figure 34. Two Figures, Suzanne Valadon, 1909

Figure 35. On the Sofa, Toulouse-Lautrec. A series of brothel scenes which show the women as people, as friends, 1886-87.

We’ll end with three paintings by Valadon of male nudes. The curators believe that Valadon was one of the first female artists to depict full frontal male nudity. Except that she didn’t get away with it. In this painting of Adam and Eve (Figs 36, 37) the artist is Eve and her lover is Adam. Rather than the traditional biblical story, it looks more like a celebration of a love affair. Originally Adam was no less nude than Eve but when Valadon wanted to exhibit the painting at the Salon des Indépendants in 1920, she was told she had to hide her lover’s genitalia, which she did with a vine leaf belt!

Figure 36. Adam and Eve (Valadon sp and André Uter), Suzanne Valadon, 1909 (vine belt, 1920)

Figure 37. Photograph of Adam and Eve before Valadon added vine leaves

In the Launch of the Net, of 1914, (Figs 38, 39) Valadon’s lover is three men. On the far right, he faces forward and was originally completely nude. Now a rope hangs in front of him, which at least looks less awkward than the vine belt.

Figure 38. The Launch of the Net, Suzanne Valadon, 1914

Figure 39. Launch of the Net, study without rope covering male on far right, Suzanne Valadon, 1914

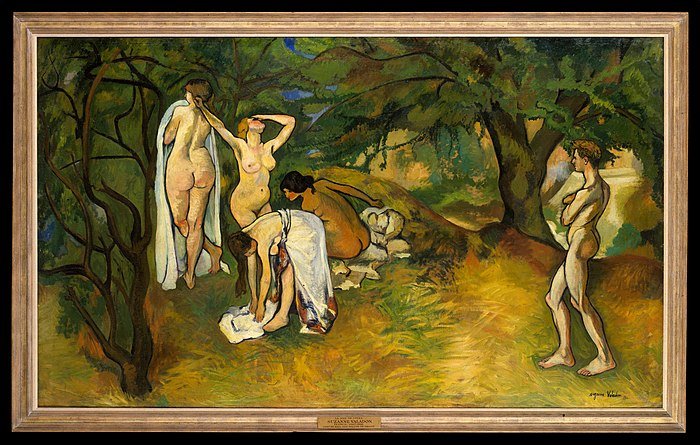

Finally, La Joie de Vivre (Fig 40) in which a nude Utter happens upon four nude women. It’s less Diana and Actaeon (41) than four women completely uninterested in the nude male standing in front of them.

Figure 40. La Joie de Vivre, Suzanne Valadon, 1911

Figure 41. Diana and Actaeon, Titian, 1559. To punish Actaeon for seeing her and her nymphs bathing naked, Diana turns Actaeon into a stag and his hounds hunt and kill him.

His gaze less aggressive because he is nude too and of course, because there are four of them and only one of him. Excellent odds!

My summary of art related abominations below. If you are not interested, just don’t read it. Gros bisous Dr. B.

Another troubling week of news. Canceling programs of diversity, equality and inclusion don’t hurt me personally. But they hurt all of us in the abstract since, by definition, narrowing what you can experience doesn’t generally make it better.

As an art historian, I can’t help but wonder about the exhibitions I have seen recently, in San Francisco and in Paris, by women artists, by artists of color, by lesbian and gay artists. How many of them would have been mounted given the current atmosphere in the nation’s capitol and in way too many states around the country.

The National Endowment of the Arts has defunded programs for under-served groups and communities saying it’s going to use that money to fund exhibitions to celebrate the 250 anniversary of the American Revolution. It’s unnecessary because it’s redundant. It’s just a way to label anyone who contests the decision as unpatriotic.

Exhibitions take a long time to mount. There are surely exhibitions in the pipeline at the National Gallery and museums around the country that receive federal funding, and they all do if they borrow works of art from other institutions, that will either just go away or find themselves at the center of unwanted controversy.

Does anyone remember the Robert Mapplethorpe exhibition that was canceled at the Corcoran Museum in 1989? Just before it was set to open? Because of partial funding from the National Endowment for the Arts, the exhibition was targeted by conservative lawmakers and their crusade against “obscene” art. After Corcoran Gallery administrators caved, “the gallery stood at the center of a firestorm of protest and controversy. Fellow artists canceled D.C. shows in solidarity, gallery members withdrew their support and hundreds of protestors gathered across from the White House, (Reagan was president) to register their disapproval.”

Will that happen again? When the inevitable exhibitions fail to meet current conservative standards? Will any institution, any artist be willing to take a stand?

How easy it has been to undo a half century of tireless work to find and celebrate artists who had previously been dismissed by the patriarchy.

What does it mean for the Kennedy Center of the Performing Arts. Trump was a no-show at Kennedy Center events last time around. This time, he fired the board of directors and named himself the president of the board. Apparently that’s legal. The board he’ll appoint will presumably give Kennedy Center life time achievement awards based upon loyalty rather than merit. Good thing Robert De Niro already got his award …..