Beef Cake and Eye Candy or The Elephant in the Room.

Bienvenue and welcome back to Musée Musings, your idiosyncratic guide to Paris and art. The subject this week is an exhibition I saw in Paris. But not one of the exhibitions I saw this past week, among them an exhibition on Suzanne Valadon at the Pompidou and an exhibition at the Cité de l’architecture et du patrimoine, on Department Stores. This was the fourth exhibition on the subject that I have seen in the past year. There was a huge one at the Musée des Arts Decoratifs, a small one at the Bibliothèque Forney and a perfect one at Musée des Beaux Arts in Caen. (I shop therefore I am) The exhibitions at la Cité are always wonderful, this one is, too. The exhibition at the Ecole des Arts Joailliers was a celebration of pearls. It was small, it was fascinating, it was exquisite. I am happy to report that there was a Proust connection! A poem on a wall written by Baron de Montesquiou, Proust’s inspiration for Baron de Charlus.

And more about my luck. I reported last week that there was a fève in each of the three slices of the three different galettes des rois I bought at Brigat the last week of January. On Sunday, February 2, Ground Hog’s Day in the United States, (Punxsutawney Phil saw his shadow, winter will be around for 6 more weeks, well 5 now) La Chandeleur here in France. (40 days after Christmas, the day Jesus was presented at the temple and people in France eat crepes) I went to Brigat for a baguette. I was surprised to see two slices of galette des rois. I bought one, of course. And I asked the woman from whom I bought it if there were fèves in every individually sold slice of galette. No, the woman said, each full galette had only one fève. I asked how many different fève types there were. Five, she said. Which meant that not every classic galette had one kind, every pecan another and every lemon cream, a third. They were all mixed up. I was very lucky to get a fève in each of the 3 slices and even luckier to get a different fève in each one. When I tried to slice the slice I bought last Sunday, my knife got stuck. Yep, another fève. Amazing. But even more amazing, it was different, it had ‘Rue des Tournelles’ on it. My French friend suggested that I buy a lottery ticket. Alas my luck stops at fèves (Fig 1)

Figure 1. My four fèves from Brigat - sitting on my Caillebotte catalogue

The exhibition on Gustave Caillebotte that I saw in Paris late last year will be in L.A. and Chicago later this year. There are parallels with the female artists whose work we have been discussing. Tamara de Lempicka who painted females both nude and clothed, sometimes alone, luxuriating in their solitude; sometimes together, sexually, sensually, sated. Tamara happily celebrated her sapphic self. Mary Cassatt painted women both dressed and dishabille. Hers are polite paintings, genteel paintings. No one ever suggested that Mary Cassatt painted women because she was a lesbian. However a recent rereading of her will reveals that she and her long time female companion, to whom she left money and canvases, were probably an item.

. Which brings us to Caillebotte as woven throughout this exhibition are references to Caillebotte’s sexual orientation. Suggestions that his paintings address something he didn’t otherwise acknowledge. Some critics found those insinuations offensive and blamed the Americans. A reviewer from Le Figaro wrote that, “The Musée d’Orsay, under the influence of its American partner coproducers, chose to study the painter’s ‘masculinity.” A writer from Libération insisted that “American-developed gender studies in art history have ‘crossed the Atlantic and landed,’ at the Paris institution.” A critic at Le Monde, wrote that “curators took a “biased” view of the artist’s practice, focusing on his more numerous depictions of men over that of women as further evidence that Caillebotte was gay.” The critics write as if this is the first time Caillebotte’s sexuality has been discussed. It isn’t. Holland Cotter, a decade ago (NYT) writing about a Caillebotte exhibition at the National Gallery, wrote, “I was struck afresh in this show by the homosocial, if not necessarily homoerotic, texture of his world… Women have only walk-on roles.”

The curator from the Art Institute of Chicago “rejected both the notion that the Americans had influenced the French in the show’s making and that it implied Caillebotte was gay. ‘I was amused, because (the critic) was saying the Americans inflicted their wokeness on Paris … the idea for this exhibition came from Paris.’” The Orsay’s curator explained, “The exhibit affirms nothing concerning the artist’s sexuality. However, it does not forbid itself from asking the question: What is the gaze of one man on another man about? [and] What is eroticism when applied to the masculine body? His subject matter is very radical .. because men were not supposed to stare at men, and he’s staring at men. It’s the elephant in the room.” (ArtNet Devorah Lauter)

Gustave Caillebotte was born in 1848 into a family of privilege. He studied law and engineering and served in the military (1870-71) before he studied art. Mary Cassatt’s father insisted that his daughter sell her paintings to support herself. Caillebotte’s father encouraged Gustave and his brothers to pursue their artistic inclinations.

Not only did Caillebotte not need to sell paintings to survive, he bought paintings from his artist friends like Monet, so that they could. (Figs 2-5 is a sampling) Until fairly recently, it was the art collection he amassed and which he donated to the French state and not the canvases he painted that attracted the most attention. When Caillebotte’s father died in 1874, Gustave and his brothers inherited their father’s fortune. When their mother died 4 years later, they inherited the rest of it and became millionaires.

Figure 2. The Ballet, Edgar Degas, 1876 (Caillebotte collection)

Figure 3. Bal au Moulin de la Galette, Auguste Renoir, 1876 (Caillebotte collection)

Figure 4. Le Balcon, Edouard Manet, 1868 (Caillebotte Collection)

Figure 5. Claude Monet, Gare Saint Lazare, 1877 (Caillebotte Collection)

Les Raboteurs de Parquet (Floor Scrapers) is the painting which Caillebotte hoped to exhibit at the Salon of 1875. (Fig 6) The Salon’s jury rejected it. Caillebotte never tried again. He joined the impressionists and exhibited this painting at the group’s second exhibition in 1876. The year Degas exhibited his Ironers. It was these two paintings that Deborah Solomon used to dismiss Mary Cassatt’s women as workers - they weren’t doing real work like Caillebotte’s and Degas’s laborers were. (Figs 7, 8)

Figure 6. Les Raboteurs de Parquet (Floor Scrapers) Gustave Caillebotte, 1875

Figure 7. Les Repasseuses, (Ironers). Edgar Degas, 1876

Figure 8. Bathing Child, Mary Cassatt, 1880

Caillebotte was one of the first artists to depict urban workers on a grand scale, a scale that historically was reserved for history and religious paintings. In this he followed the lead of realist painters like Millet and Courbet who painted scenes of rural men and women doing backbreaking work. (Figs 9, 10) Caillebotte knew the workers he depicted, they were employed by the artist's family. And he knew the place, it was his future studio.

Figure 9. The Gleaners, Jean-Francois Millet, 1857 (collection left-over hay)

Figure 10. The Stone Breakers, Gustave Courbet, 1849

A painting of men, half nude and on their knees, (Fig 11) it’s not surprising that one reviewer sensed a sexual energy, ‘The artist seems to have been visually delighted by the rippling, lean muscles of these ‘everyday men’…’ The curators’ interpretation is that the artist, a bourgeois, identified with these men. Because like them, he was a hardworking guy doing manual labor. They see it as Caillebotte’s way “to escape his condition as a wealthy rentier (landlord) and (find) fulfillment in the brotherly bonds he forged with men from other milieux.…” Caillebotte occupies the best of both worlds He stays neat and clean while he paints sweaty laborers at his feet, doing the job he has paid them to do. Because someone is the landlord and someone is the laborer.

Figure 11. Les Raboteurs, detail, Gustave Caillebotte

Another painting, The House Painters, from 1877, (Fig 12) also depicts working men. One on a ladder, another on the ground, pause to consider the facade of a shop they are painting. Caillebotte shows them as artists examining their work on a wall just as an artist examines their work on a canvas. The curators contend that Caillebotte identified with these men, too. Their loose-fitting jackets are similar to a painter's smock. (Fig 13) Both permitted freedom of movement and were very different from the narrow frock coats and morning coats that upper-middle class gentlemen wore.

Figure 12. The House Painters, Gustave Caillebotte, 1877

Figure 13. Smock and straw boater (as worn by painter on ladder, Fig 12)

This building was probably opposite the mansion where Caillebotte and his brother Martial lived on rue de Lisbonne. Pinpointing an exact location for this scene and others is possible because of Michael Marrinan 2017 monograph on Caillbottte in which he used notarial documents and city archives to locate Caillebotte’s street scenes. The exhibition includes maps to establish locations of Caillebotte’s paintings. Costumes on display help distinguish what men of different ranks wore and when and where. (Figs 14-15a)

Figure 14. Detail of map showing locations of Caillebotte residences and painted scenes

Figure 15. Gentleman’s attire

Figure 15a Man (René Caillebotte) at the window, wearing same outfit as above, Figure 15, Caillebotte

Following the death of their mother, Gustave and Martial (René another brother was already dead, at 25, probably a suicide) sold the family mansion and moved into a large luxurious apartment on the fourth floor (with elevator) of a grand building on Blvd Haussmann. The painting ‘Bezique Game’ (Fig 16) depicts Caillebotte’s friends and brother in a salon, playing cards. We’ve all seen enough impressionist paintings to know that interiors were the domain of women. Depicting men indoors was rare, indoors without women, rarer still. Women dominated the private sphere of the home, (Figs 17, 18) men dominated the public sphere of the street. Caillebotte, according to the curators was “keen to illustrate the more intimate - or "feminine" facet of middle-class men who while away the time playing cards (and) watching the city from their balconies.”

Figure 16. Partie de Bésigue (Bezique Game) Gustave Caillebotte, 1880

Figure 17. The Tea, Mary Cassatt

Figure 18. Reading, Berthe Morisot

‘Balcony Boulevard Haussmann’ (Fig 19) is set on the very long balcony of the Caillebotte brothers’ apartment. Men looking out windows (above Fig. 15a) was a traditional motif in paintings, men standing on a Haussmannian balcony was a riff on this motif. Standing on a balcony, with a bird’s eye view, allowed these men to survey all that was below. They could regard the cacophony of the street without mingling with the crowds. Tamar Garb interprets the scene through a sexual lens. “It depicts two men from obviously different class and social backgrounds..,” The only reason they are “on a balcony together in 1870s Pairs is a homosexual affair,” She explains that because of public concern about homosexual relations in late 19th century Paris, upper middle-class men avoided sexual relationships with each other. Homosexual encounters with men of the lower classes or prostitutes permitted the view that homosexuality was purely physical, not emotional.

Figure 19. Balcony, Boulevard Haussmann, Gustave Courbet

Rainy Day in Paris (Fig 20) was the hit of the 1877 Impressionist exhibition. It’s Caillebotte’s largest painting. The main figure, his overcoat unbuttoned, holds an umbrella in one hand and nonchalantly keeps his other hand in his pocket. With a woman on his arm, he exudes a sense of self-assurance. For the curators, this figure is the artist’s embodiment of an “ideal form of bourgeois virility and accomplished masculinity.”

Figure 20. Rainy Day, Paris, Gustave Caillebotte, 1877

There is not a one to one correlation with the painting’s location, an intersection near the Gare Saint-Lazare. (See above Fig. 5) That’s because Caillebotte introduced uniformity to the building facades when there was none, which required manipulating the buildings’ proportions as well as perspective. In a review of Marrinan’s book, Elizabeth Benjamin writes that this particular spot had a dual significance for Caillebotte - it was where old and new Paris joined and it was the space through which Caillebotte passed from his family’s haute bourgeois mansion to the social life he shared with the Impressionists. This painting and other urban scenes by the artist, with large format and complex spatial constructions ‘elevate modern life to the heroic status of history painting.’

In the painting Le Pont d’Europe, (Fig 21) Caillebotte takes center stage as the flaneur coming toward us. He is not with the woman near him. His gaze is directed to the man leaning on the railing. Again according to Tamara Garb, “This intentional distance between the flaneur and his female counterpart diminishes their sexual connection, leaving the flaneur open to other possibilities…” Unlike most Impressionist paintings which idealize fashionably dressed women, in this painting, it’s the man in workman’s clothes leaning nonchalantly who is the object of the flaneur’s gaze.

Figure 21. Le Pont de Europe, Gustave Caillebotte

Man at His Bath of 1884, (Fig 22) the curators believe revolutionized the genre of the male nude. Before this, male nudes were either studio drawings or idealized nudes in history painting. (Fig 23) This man is real although we don’t know his name or his connection with Caillebotte. We do know that the bath he has just gotten out of was in the artist's bathroom at his country estate. Of course Caillebotte knew Degas’ paintings of nude women getting into or out of the bath, or drying themselves off in awkward, ungraceful poses. (Fig 24) This is different. The curtain in front of the man provides privacy. But not from us. We observe him from behind, drying himself off, his legs shoulder distance apart, a bit of genitalia visible, to those of us willing to look closely enough. Observing a nude man from behind and without restriction, how could there not be an erotic reading. The painting was exhibited in 1888, in Brussels, at an exhibition organized by the avant-garde "XX group”, where it was relegated to a back room.

Figure 22. Man at His Bath, Gustave Caillebotte, 1884

Figure 23. Leonidas at Thermopylae, J. L. David

Figure 24. After the Bath, Edgar Degas

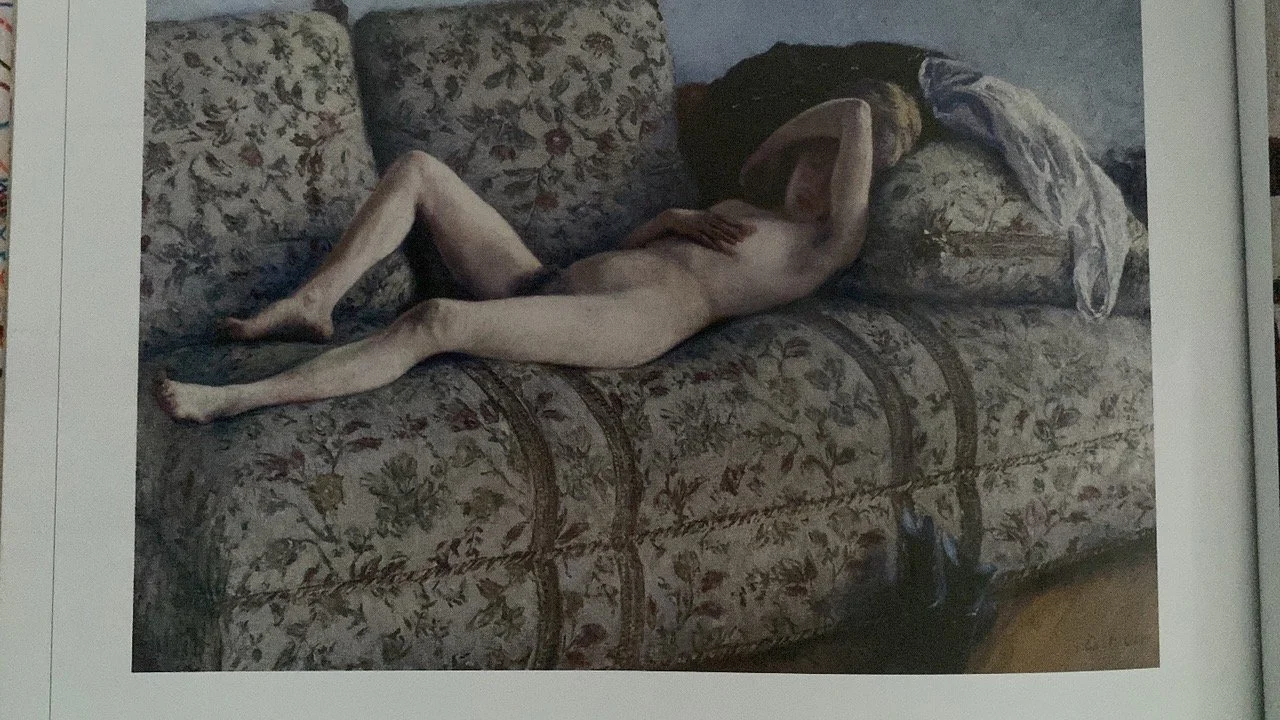

This is one of three paintings of nudes by Caillebotte from the 1880s. Another depicts a man sitting on a chair beside the same bath, drying his uplifted leg. A third is a young woman, lying on a sofa, pale and listless. (Figs 25, 26)

Figure 25. May Drying Leg, Gustave Caillebotte

Figure 26. Female Nude, Gustave Caillebotte

Caillebotte was a passionate sailor and gardener, activities he pursued when he moved permanently to the countryside. He kept painting, of course but he stopped exhibiting. Unlike his fellow Impressionists, the countryside for Caillebotte wasn’t about sailing parties or luncheons at taverns where the focus was the women’s frocks. (Fig 27) Caillebotte painted men-only sports, like fishing and rowing and diving on the Yerres, (Fig 28) the river that ran alongside the grounds of his country house. This painting of a rower from the vantage of someone sitting on a facing seat is a very tight arrangement. (Fig 29) Tamara would have approved.

Gros bisous, Dr. B.

Figure 27. Luncheon of the Boating Party, Auguste Renoir

Figure 28. Three River Scenes (fishing, diving, rowing) Gustave Caillebotte

Figure 29. Oarsman in a Top Hat, Gustave Caillebotte, 1877-78

Bonus - a taste of Caillebotte’s flower paintings, to learn more, see: Art as Decoration

IMHO 1. Diversity doesn’t lower standards, legacy and entitlement do. The playing field is not even but the culprit is not minorities and women, it’s rich white men buying, not earning, the positions they assume. 2. Do we really want someone who bought something for $44 billion (Twitter) that is now worth $9 billion (X), making critical decisions about the federal government? Playing with other people’s lives is what these guys do.

New comment on Auto Eroticism: Girls in Cars, Driving Fast:

Beverly, it just occurred to me that a close and careful study of the body of your Musée Musings would reward the student with a high degree in art history. I’ll forever think of you as “Professor B”! Morris, N. Carolina

Dear Beverly,

my warmest congratulations on your finest Musee Musings yet, from the splendid galettes, which made my mouth water while far off in distant Florida. to the wondrous work of Tamara. How many appetites can you satisfy in one gulp? You actually took my mind off the impact of Trump for a good twenty minutes, even though my Canadian hosts are tearing their hair and rending their garments. warmest regards and best wishes to you and your lovely daughter, Martin, D.C., & Dordogne

Thank you so much for your in depth look at Tamara de Lempicka's life and work. I had never heard of her before seeing a recent segment of CBS Sunday Morning, which can be viewed here: https://youtu.be/Ga3LpKbNy9k?si=KiGErFoARJqI1sol Your information brings so much more depth to the life and works of a fascinating artist. I am entranced by her ability to create such a satiny, glossy look in her paintings. I want to run my fingers over those fabrics! Also, you have an amazing talent for sharing local foods with us... I am dying to try all those galettes du roi, and you made perfect choices. It looks like you have much good fortune coming your way, and deservedly so! Your own blog entries are a delight to our senses!! Thank you for sharing these experiences and your expertise with us! Bonnie, N. Y

DR. B! THE TAMERA DE LIMPICA EXHIBIT, I FOUND TO BE EXCELLENT 1

I FEEL WE HAVE OVERLOOKED WHAT WOMEN OF THAT ERA GAVE UP TO BREAK OUT OF THE BOXES...IMPOSED BY MOST SOCIETIES OF THE JAZZ AGE/ART DECO.

THIS WAS A GREAT HEADS UP AS TO WHAT WE OWE THEM...we stand on their shoulders. Merci, Jacquelyn, Bay Area, CA